The house on Sunset Boulevard was inconspicuous. Set back from the street, it could barely be seen but the house was a deep lot, with tennis court in the back where Lloyd Shearer, editor of Parade Magazine in its heyday would regularly interview a Who’s Who of celebrities. Sagan brought a story with him…

A Story that Had to be Told — and Remembered

Your editor of Strategic Demands was a student at the University of Southern California when I met Lloyd ‘Skip’ Shearer, an intense man who conducted the business of Parade from his home. I became a regular visitor at the Sunset house as a friend of his sons, Cody, a journalist like his father and Derek, a social activist, educator who went on to become US Ambassador to Finland and Lloyd’s daughter Brooke, who would marry Strobe Talbott.

Strobe is a story in himself of course, having lived in England as a grad student with Bill Clinton and having accompanied Bill to Russia, where Strobe came away with pages from Nikita Kruschev that Strobe edited and translated into Khruschev Remembers.

But let’s pick up the story with one of the visitors to Lloyd’s house, Carl Sagan, and let’s revisit one of the most important messages carried by Carl to the world through the efforts of Skip Shearer and Parade. The story? How the end of the world could visit each of the world continents, one after another.

The story is one I became versed in — first as a debater and a friend of Congressman George E. Brown in the ‘duck and cover’ era. As a young thinker I argued nuclear proliferation, winning and losing high school debates in California as we envisioned humanity’s future. On the Beach was on my reading list and we understood with sirens going off nearby that a global nuclear disaster was truly not far from reality.

Let’s leave those stories for now, we’ll return, but for now let’s begin with the introduction of what happens after a nuclear exchange… the science of atmospheric disruption, whether as a result of full-out nuclear war or ‘regional’ conflict, is much more certain than in days past, but the risks of nuclear disaster have strayed far from day-to-day understanding and public writing, demonstrations, demands for nuclear weapons treaties and arms control.

“When Carl Sagan Warned the World About Nuclear Winter”

By Matthew R. Francis of Smithsonian.com

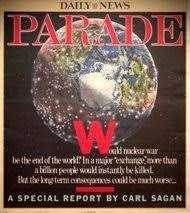

November 15, 2017If you were one of the more than 10 million Americans receiving Parade magazine on October 30, 1983, you would have been confronted with a harrowing scenario. The Sunday news supplement’s front cover featured an image of the world half-covered in gray shadows, dotted with white snow. Alongside this scene of devastation were the words: “Would nuclear war be the end of the world?”

This article marked the public’s introduction to a concept that would drastically change the debate over nuclear war: “nuclear winter.” The story detailed the previously unexpected consequences of nuclear war: prolonged dust and smoke, a precipitous drop in Earth’s temperatures and widespread failure of crops, leading to deadly famine. “In a nuclear ‘exchange,’ more than a billion people would instantly be killed,” read the cover. “But the long-term consequences could be much worse…”

According to the article, it wouldn’t take both major nuclear powers firing all their weapons to create a nuclear winter. Even a smaller-scale war could destroy humanity as we know it. “We have placed our civilization and our species in jeopardy,” the author concluded. “Fortunately, it is not yet too late. We can safeguard the planetary civilization and the human family if we so choose. There is no more important or more urgent issue.”

The article was frightening enough. But it was the author who brought authority and seriousness to the doomsday scenario: Carl Sagan.

One of the more enlightening and uplifting messages of Carl Sagan, as he spoke of the imminent threat of a ‘doomsday scenario’, was the message he brought about humanity’s origins in the stars.

His was a message of life in the face of death.

“Our posturings, our imagined self-importance,

the delusion that we may have some privileged position,

are challenged by this point of pale light.

Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark ….

There is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

This distant image of our tiny world…

underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another,

and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve got.”

–Carl Sagan

And then there are the religious leaders who speak of threats to life — of nuclear weapons at the apex of this clear and present danger, this threat to life on earth as we know it.

Take the Catholic pontiff as one voice in the wilderness as he brings his message to his flock and the world.

The Pope and Catholic Radicals Come Together Against Nuclear Weapons

When something difficult is attempted,” Daniel Berrigan said, “it is like trying to break a rock with an egg.” Berrigan, a Jesuit priest and social radical, who died in 2016, at the age of ninety-four, spent the last third of his life doing something difficult: trying, through protest, civil disobedience, and a steady stream of books and articles, to persuade the nuclear powers to abolish their arsenals. For his efforts, he was frequently called an out-of-touch extremist who changed nothing. But now, when the jousting of Donald Trump and other would-be political strongmen on the world stage are making the nuclear threat appear particularly urgent, there are signs that the Catholic Church has come around to the position that Catholic activists such as Berrigan have resolutely maintained for the past four decades.

Pope Francis… will turn his focus to nuclear weapons later this month, when he visits Hiroshima and Nagasaki—the cities where, in 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs—killing, by some estimates, a hundred and fifty thousand people and seventy-five thousand people, respectively.

Nagasaki has been the historic center of Japan’s Catholic community since the sixteenth century, and on Sunday, November 24th, Francis will give a public address at the ground-zero site of the nuclear attack on the city. Echoing past Popes, he will doubtless denounce nuclear weapons as a threat to humanity, and their ongoing development as a grave misallocation of wealth and resources. Then he’s expected to go further.

Twice in 2017, in diplomatic contexts, Francis made remarks that moved the Church away from its support of nuclear deterrence and toward advocating for the abolition of nuclear weapons and condemning their “very possession.” In Nagasaki, according to Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s secretary of state, Francis will place the authority of the papal office, along with his immense personal authority, in support of that objective and call for the “the total elimination of nuclear weapons.”