Iran nuclear deal a win for non-proliferation …

The issues of 21st century nuclear proliferation — and next generation ‘smart’, modernized nuclear weapons — introduce next generation risks of strategic, tactical, and accidental nuclear war.

The lessons of the 20th century nuclear conflagration with MAD “mutually assured destruction” delivering a mortal flash point, followed by worldwide nuclear winter and environmental processes bringing extinction, have receded into memory, principally as a result of several decades of non-proliferation agreements and nuclear arsenal draw downs.

Unfortunately, this is changing as we witness a younger generation without personal memory of the Cold War — or its close calls. The temper of the times is shifting and nuclear weapons and attendant risks are rising even as non-proliferation voices are raised and new agreements are put forward.

Nuclear non-proliferation is facing a broad-based threat and nuclear escalation is on the horizon. ‘Usable’ nuclear weapons such as the B61-12 ‘beyond gravity’ guided missiles are being prepared for deployment, circa 2020, and their advanced delivery systems, nuclear-weapons configured, “penetrating” F-35 fighters, are scheduled to be deployed to Europe and Asia. The budgeting in the U.S. Congress and final testing phase is in process, even as existing non-proliferation treaties are being set aside amid recriminations. Operational imperatives are being set in command-and-control action. Think tanks are rumbling with threats and counter-threats.

Russian and Chinese military systems are responding. A new version of the previous century’s ratcheting up of nuclear confrontation is now underway, with modernized MIRV’d ICBM/SLBM missiles, tactical cruise missiles, and policies that no longer speak directly to consequences.

In contrast, there is a religious-drive toward envisioned Armageddon-esque prophecies popularized in the sales of tens of millions of books by apocalyptic writers such as Accinni, Becker, Choufati, Cronin, Hagee, Jeremiah, LaHaye, Lindsey, Yulish… the list goes on.

Christian Evangelicals and millions who profess belief in Biblical-related revelatory passages speak of the “End Times” with pretribulation, premillennial, Christian eschatological and end of the world visions often professing nuclear war and support for political figures who speak of the Mideast with biblical fervor as a ground-zero for forces that will bring salvation to believers — and disaster to non-believers.

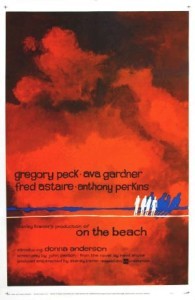

Perhaps it is time to recall another book — a novel turned into On the Beach …

With nuclear war and its aftermath in mind, the following editorial point-of-view has special timeliness, posted where On the Beach takes place … Down Under.

§

by Chris Patten for The Australian

JULY 20, 2015

Let us give praise where it is richly deserved. Despite all the criticism they faced, US President Barack Obama and his Secretary of State, John Kerry, stuck doggedly to the task of negotiating a deal with Iran to limit its nuclear program. Together with representatives of Britain, Russia, China, France, and Germany, they have now succeeded.

The main terms of this historic agreement, concluded in the teeth of opposition from Israel, Iran’s regional competitors (particularly Saudi Arabia), and the political Right in the US, seek to rein in Iran’s nuclear activities so that civil capacity cannot be swiftly weaponised. In exchange for inspection and monitoring of nuclear sites, the international economic sanctions imposed years ago on Iran will be lifted.

This is a significant moment in the nuclear age. Since 1945, the terrifying destructive force of nuclear weapons has encouraged political leaders to search for ways to control them.

Not long after the destruction of Hiroshima, US president Harry Truman, together with the Canadian and British prime ministers, proposed the first non-proliferation plan; all nuclear weapons would be eliminated, and nuclear technology for peaceful purposes would be shared and overseen by a UN agency. Truman’s initiative subsequently went further, covering most of the non-proliferation issues that we still discuss today.

But the proposals ran into outright opposition from Joseph Stalin, who would accept no limit to the Soviet Union’s ability to develop its own nuclear weapons.

So the nuclear arms race began, and in 1960 president John Kennedy warned that there would be 15, 20, or 25 nuclear states by the mid-1960s. “I ask you,” he said in 1963, “to stop and think for a moment what it would mean to have nuclear weapons in so many hands, in the hands of countries large and small, stable and unstable, responsible and irresponsible, scattered throughout the world.”

Two developments averted the nightmare of reckless nuclear proliferation. First, several countries capable of developing nuclear weapons concluded — in some cases, even after launching programs — that to do so would not increase their security. To their credit, South Africa and a number of Latin American countries took this route. Second, self-denial was greatly reinforced by the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, negotiated after the 1962 Cuban missile crisis and administered by the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Since entering into force in 1968, the NPT has been central to holding the line on the spread of nuclear weapons. Nowadays, apart from the original nuclear powers — the US, Britain, France, and Russia — the only other countries with these weapons are China, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea.

The Iran negotiations were vital to ensuring the integrity of the system. The danger, of course, was that Iran would move from developing civil nuclear power to making its own weapons. This would inevitably have caused other countries in the region, probably beginning with Saudi Arabia, to go the same way.

There is an important lesson to be learned from more than a decade of negotiation with Iran. Iranian President Hasan Rowhani was his country’s chief nuclear negotiator from 2003 to 2005. Iran’s president at this time was the scholarly moderate Mohammed Khatami, with whom I at one time attempted to negotiate a trade and co-operation agreement on behalf of the EU. Progress was stopped by disagreement over nuclear matters.

Khatami’s attempts to open a dialogue with the West fell on stony ground in US president George W. Bush’s Washington, and eventually he was replaced by the populist hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. But in Rowhani’s discussions on proliferation back then, Iran had offered the three EU countries with which it had begun negotiations a reasonable compromise: Iran would maintain a civil but not a military nuclear capacity. This would have capped the number of centrifuges at a low level, kept enrichment below the possibility of weaponisation, and converted enriched uranium into benign forms of nuclear fuel.

The British representative to the IAEA at this time, ambassador Peter Jenkins, has said publicly that EU negotiators were impressed by Iran’s offer. But the Bush administration pressured the British government to veto a deal along these lines, arguing that more concessions could be extracted from the Iranians if they were squeezed harder and threatened with tougher sanctions and even a military response.

We know how the Bush strategy turned out. The talks collapsed: no compromise, no agreement. Today, a deal has been concluded; but it is less good than the deal that could have been reached a decade ago — a point worth keeping in mind as the likes of former vice-president Dick Cheney and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu start hollering from the sidelines.

As it is, not only will an agreement add cement to the NPT; it could also open the way to the sort of understanding with Iran that is essential to any broad diplomatic moves to control and halt the violence sweeping across western Asia.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Chris Patten, a former EU commissioner for external affairs, is Chancellor of the University of Oxford